Room for One More

I didn’t mean to make my grandma cry.

Seated around my grandparents’ kitchen table, her mouth froze mid-bite, and she sat the half-eaten blueberry muffin down on her plate. My mother was in her 30s, and asked her to tell the ten-year-old version of myself about our ethnic heritage.

“Leslie, we don’t talk about that.” Grandma pushed away from the table; the feet of her chair screeching against the linoleum floor. She rushed out of the kitchen, feet pounded up the wooden steps, past the hallway’s wallpaper painted with green ivy, and into her bedroom.

Her husband, Grandpa Roger, kept chewing on a blueberry and shrugged his shoulders, “She’s a redhead, you know!”

That day I learned something that my great grandmother and her daughter, my Grandma Grace, had been instructed to never talk about—we are ethnically Jewish.

Grandma Grace’s mother, Sarah, was only a teenager when she boarded a large ship bound for Ellis Island from the Netherlands—this moment captured in a black and white photo on my mother’s bookcase. Her father, Maurits, is skinny with spectacles and wearing a black suit. Sarah wore a brown linen dress, cinched at the waist. Her hair is twisted back in a style I often saw in the Anne of Green Gables episodes I consumed as a child on The Disney Channel. Next to Sarah, stands her little brother and sister, Leo and Teresa. She’s nearly a decade older than them and her hand rests on their small shoulders—as if protecting them from the huge life transition ahead.

A picture of my Great Grandma Sarah (right), and her siblings Teresa and Leo while growing up in the Netherlands.

It was 1906 and Sarah was only 14, but anti-Semitism became a national reaction to the large influx of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Before Jews gained more acceptance on American soil after World War II, they were considered low-class and untrustworthy; not allowed into elite colleges, clubs or to purchase homes in nice neighborhoods. Our great American car-maker, Henry Ford, published articles blaming the Jews for creating World War I in order to profit. The resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan in 1915 added a hatred of immigrant Jews and Catholics to its anti-black ideologies.

My Great Grandma Sarah was 23 years old when men gathered across the United States in white pointed hats, faces covered, united in a hatred of people like her, Maurits, Teresa and Leo. Psychologists say that the body keeps score of our fears and trauma, and it seems my Grandma Grace inherited the shame of our Jewish heritage while growing in Sarah’s womb.

During her first years, Sarah did everything to become unnoticeable in American society. She worked to lose her Dutch accent, and traded simple shoes for the style of young women in 1910—pointed leather boots with two-inch-high heels. After attending a revival service at a local church, Sarah converted to Christianity—something her Jewish father disapproved of but refused to hinder.

I imagine her young and alone, sitting in the wooden pews of the Methodist Church on Sunday mornings. And while Sarah grabbed at other changes to “fit in,” her conversion to follow the Christian Jesus grabbed her heart.

As a young wife and mother, Sarah started a weekly Bible study for young ladies that were once like her; starting their journey of faith.

Although it wasn’t a catchy name, she called her Bible study: Room for One More. My Grandma Grace said their living room sofa and chairs were packed with young ladies. Some played their banjos and ukuleles while singing hymns; their laughter and prayers echoing through the house.

Of course, as the mother of three, Sarah’s home, schedule and heart became crowded, but she wanted to remind both herself and the girls—there was always room for one more.

One more person at the dinner table. One more conversation in our busy schedule. One more individual who needs to be noticed and invited in.

Sarah had a button made that she and all the girls in her Bible Study pinned on their white collars. It was simple and had four letters: RFOM—Room For One More.

Some of the girls in Sarah’s Bible Study—Room for One More—sitting on the steps of her home in St. Louis, MO. My Great Grandma Sarah is sitting in the middle row, far right, with my Grandma Grace sitting in front of her as a child—her head turned, likely talking, making the teen next to her laugh.

Inside, I live with a constant dichotomy—both fragile and strong. Lately, I’ve felt more breakable than enduring. And when I feel threatened, I collapse my world. It becomes small. I become small. My hurts and healing consume me—crowding out room for anyone else.

*****

My parents lived and worked in the Netherlands for two decades, and I often visited the homeland of my Jewish Great Grandma Sarah. As a girl growing up in Missouri, my Wednesday night church group read a book, The Hiding Place, by Corrie Ten Boom. Corrie’s family were Dutch watchmakers who decided to use a secret room in their apartment above their shop in Haarlem to hide Jews as they fled Nazi deportation.

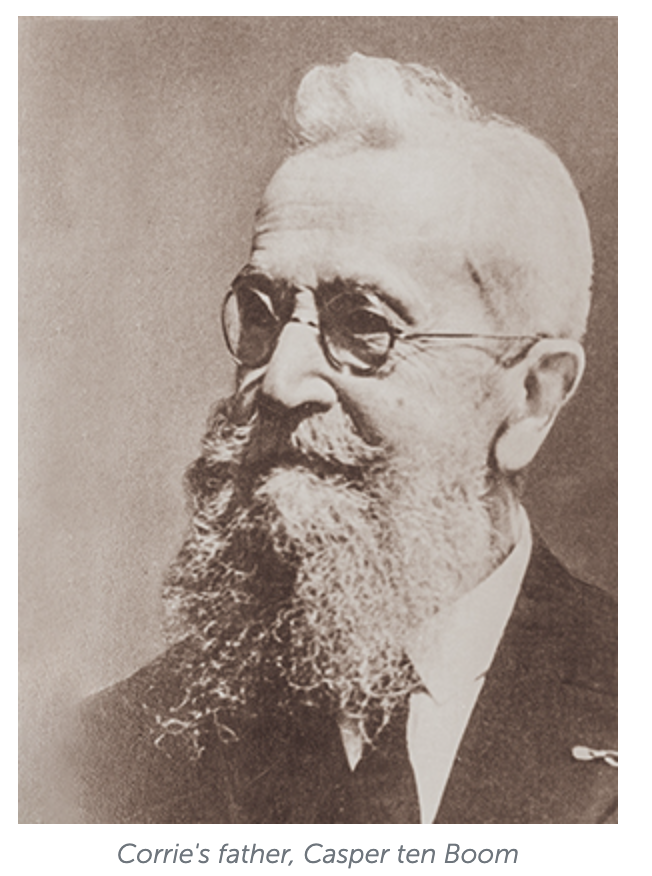

The Ten Boom family rescued over 800 Jews from death until they were caught and sent to a German concentration camp alongside those they tried to save. After ten days in the camp, Corrie’s father died. Corrie and her sister, Betsie, returned after hours of forced labor to lead groups of women in worship and Bible study around a tattered Bible smuggled into the camp. Betsie’s health deteriorated, and after enduring ten months, she died.

Corrie recorded some of Betsie’s final words: “There is no pit so deep that God is not deeper still.”

Twelve days later, Corrie was released by mistake, due to a clerical error—one week before all the women her age were killed in the gas chambers.

****

The final years my parents spent in the Netherlands, they lived in the city of Haarlem and I visited the Ten Boom Watch Shop and apartment that is now preserved as a museum.

I entered the store’s corner door and joined a group of people waiting around display counters filled with old watches. I walked around the show room, pretending to look at the antiques as a way to protect myself from small talk with strangers.

But in my isolation, I knew I was being watched.

The day’s tour guide approached and leaned over the counter. She whispered above watches resting in dust beneath glass: “You’re Jewish, aren’t you?”

Unlike my Grandma Grace, the piece of chewed gum did not drop out of my mouth. I didn’t push away from the counter and run out into the cobblestone streets. My green eyes met hers.

Generations of secrets stood around me. “Yes, I am part Jewish. My Great Grandma immigrated as a Dutch Jew from the Netherlands to America.”

“I knew it,” she smiled as if she was a master detective once again proven right. “I’ve been a tour guide here for decades and I can always tell when someone has Jewish heritage. There is something special in the eyes.”

While researching for this post, I found a picture of Corrie Ten Boom’s father—the man who risked everything to make room for one more life to save. And I noticed something in his eyes: a wisdom, a clarity, a deep kindness. And I thought…

Maybe someday I can have eyes like his.

Maybe someday I can I have eyes like my Great Grandma Sarah.

Despite rejection.

Despite making myself safe and small.

Despite a worry that there could be a pit so deep and dark that God could not rescue me.

Still…I inherited something special in my eyes.

You did too…

Eyes looking to make room for one more.